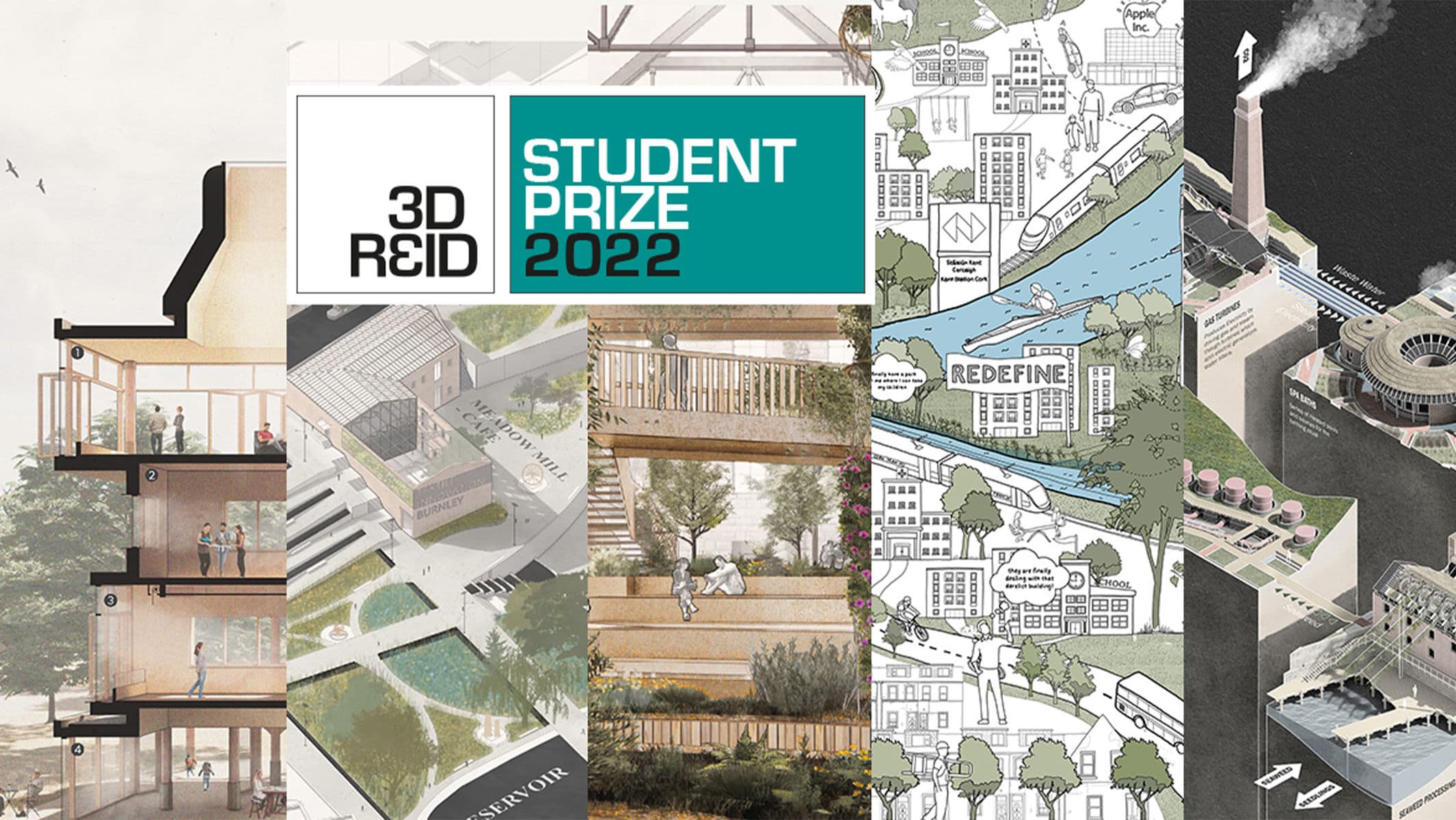

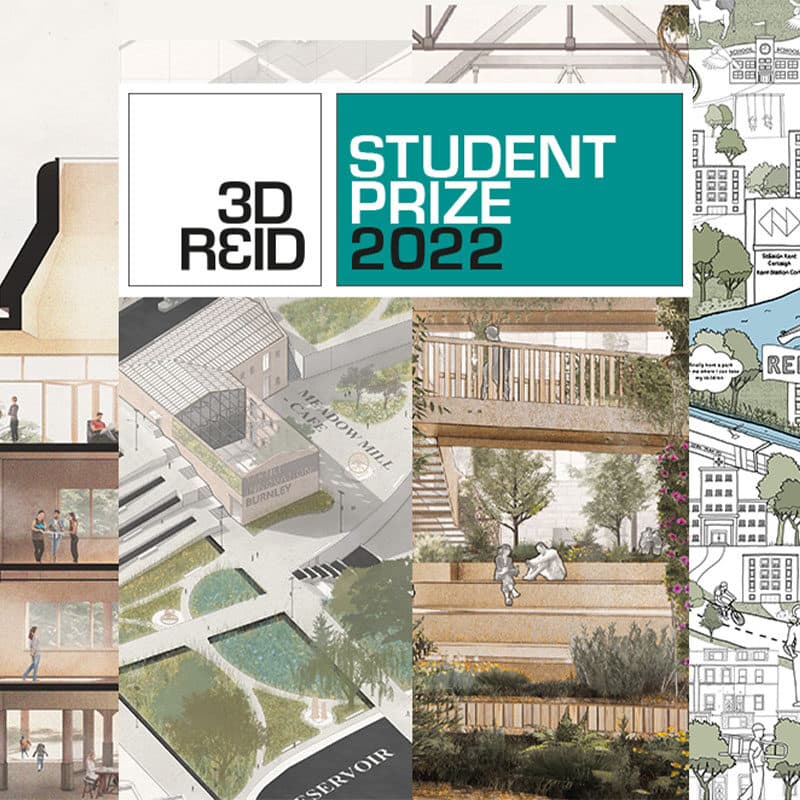

Following an internal shortlisting from 32 entries, we are delighted to announce the finalists for this year’s student prize:

- Adam Jones, Alex Cammack, Annabelle Tang, Chloë Clacy, Filip Suszczynski, Frank Kalume – University of Bath

- Jack Arnold – Leeds Beckett University

- Jonathan Edwards – De Montfort University

- Jamie Hole, Ffion Douglas, Conor Foster, Holly Knight-Parfitt – Liverpool University

- Elliot Forster – Sheffield School of Architecture

We are also delighted to be joined by a student from Ukraine, Maria Suprun, from Kharkiv School of Art, who will present remotely. The students of KhSA have been displaced from Kharkiv to Lviv midway through the current academic year, as a result of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. The university are seeking financial support to ensure the students can complete their studies and be the crucial actors in Ukraine’s future supporting displaced people and reconstructing the country. To support them follow the link Support KHSA – ХША (kharkiv.school)

We removed all names and universities from the nominations to ensure bias plays no part in the shortlist selection. We are delighted with the variety of projects in our shortlist that reflect our new judging criteria this year:

- Impact– does the project have meaning? does it address societal concerns such as environment, culture, community, wellbeing, inclusivity and marginalisation?

- Innovation – does the project represent new ways of thinking? does it explore new technologies, materials, building methods, sense of place and environmental impact?

- Communication – does it speak to the viewer? are the imagery and words well-conceived and have they embraced new ways of communicating their ideas?

The finalists will present their projects to a panel of judges on Wednesday 20th July. Below are the student submissions that have made it through to the final:

University of Bath

Adam Jones, Alex Cammack, Annabelle Tang, Chloë Clacy, Filip Suszczynski, Frank Kalume

Cork City Masterplan

Regenerate & Redefine

This proposal was completed as part of the group masterplan project within the MArch degree at the University of Bath, addressing the theme of ‘Sustainable Cities’. Following a study trip to the city of Cork, a number of key existential and experiential issues facing the city were identified; the ‘Regenerate and Redefine’ masterplan was developed to address these challenges, and ultimately, restore the heart of the city.

By respecting and celebrating Cork’s past, whilst recognising the necessity to reconsider urban living, this proposal aspires to create a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable future for Cork City. In recognising the city’s civic identity as the historical relationship with water, the masterplan identifies two key entities; the existing city centre, an urban environment rich in heritage and culture, and the South City Docks, a brownfield industrial site. Through connecting these differing entities, although contradictory in nature, the masterplan seeks to work as one complimentary urban system.

Six headline strategies were established to characterise the interventions and form a phasing strategy for the masterplan over the next 30 years. These strategies are applicable at a variety of scales, addressing both the existential threats facing the wider city and the experiential issues identified within the character zones. Although independent in nature, the interventions seek to work as one collective integrated approach, nurturing a symbiotic relationship between the contrasting entities, and thus celebrating the historic significance of the River Lee.

The proposal primarily seeks to ‘regenerate’ the existing city centre, encouraging people to relocate back into the historic core of the city. The renovation of derelict buildings aspires to celebrates the existing city fabric whilst also addressing the immediate housing crisis. Through also removing the car from the city, and prioritising the pedestrian, the masterplan improves the quality of both the public realm and environmental condition.

The masterplan also looks to ‘redefine’ the South City Docks, transforming the former industrial brownfield site into a new vibrant district for the city. The Marina Park, that once occupied the site, will be reinstated, providing the people of Cork with a meaningful and much needed public park. Throughout the biodiverse park, key buildings are retained and converted to provide purposeful functions, creating a series of dynamic public attractions. An exciting mixed-use development will also provide high quality dwellings, workspace and public infrastructure; all components of inner city living necessary for the sustainable growth of Cork city.

Leeds Beckett University

Jack Arnold

Weathering the Monsoon

Video file to be viewed alongside drawings

Despite the unsurmountable damage caused by the annual monsoon to rural communities all across India, there is still no clear architectural response to this extreme but entirely predictable climatic condition contrary to other areas of southeast Asia.

Whether this is due to a lack of acknowledgement from government or just a lack of construction skillset, it is the poorest communities that will continue to suffer in even greater numbers as climate change amplifies the scale of damage. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, in 2020 alone, flooding throughout India caused over 929,000 instances of internal displacement, that’s the equivalent of the entire population of the Leeds Bradford area being left without home or shelter during some of the most unrelenting climate conditions experienced on earth.

This design thesis seeks to propose new monsoon resilient architectural typologies for some of the poorest rural communities in Tamil Nadu. Grounded within the flood zone of Matrikunj this project centres around a construction campus which provides the space and tools to upskill local people to enact their own positive architectural change. The site will also provide emergency shelter to victims of the monsoon in the form of a flood resilient satellite village surrounding the campus.

The project is implemented through a series of interconnected kinetic floor systems designed to rise and fall with the water table on site. Parametric software has been utilised in order to allow for high data input and management of form. The kinetic branch network within the floor system connects to float wells recessed into the ground that fill up with water before the site begins to flood, in turn raising the floor plate before any flood water can cause damage. This floor plate then forms the foundation from which a community can build upon.

Overall, this project aims to restore dignity to local communities by providing a safe space to rebuild their lives above the flood waters.

De Montfort University

Jonathan Edwards

Lost Wales – Reviving Porth Wen

Looking at Wales’s industrial past, this project attempts to repurpose an abandoned brickworks on the island of Anglesey to create a hub for seaweed bio-energy production accelerating the UK’s transition to sustainable power. The recent energy crisis has highlighted an important yet impending need for a self-sustaining regional green method of generating electricity. The scheme proposes, Britain should look to its vast area of coastal waters to create a new energy ecosystem. The project also looks at how seaweed can be used to promote a new green economy that empowers local communities with skills to revive their fragmented and lost post-industrial landscapes. To test this idea, a coastal industrial ruin was chosen in Anglesey, an area envisioned to be Britain’s ‘energy island’ by the government and transformed into a small industrial seaweed hub. The design envisages a circular economy in which seaweed is grown and harvested to be used to create energy as well as products for the wellness industry. This will create an opportunity to create tourism beyond its seasonal offering into a year-round activity centering on a spa. The design of the spa celebrates Anglesey’s industrial past while funding its future.

The two programs work in conjunction with one another as the powerplant produces energy and hot water while the spa funds the research, creates industry for making products and operations of the energy plant. A facility where biogas energy is researched and developed is on site, so that the most affordable and efficient way of generating electricity is developed. This may include testing different seaweed species, changing anerobic digestion temperatures, and utilizing different turbines. Eventually, this experiment will be scaled up to another local site where the green seaweed economy can begin to power the whole island. The spa is a more permanent intervention celebrating the areas beauty while protecting the fragments of its previous life. It is inspired by the materials and construction of the Welsh vernacular style, including the incorporation of seaweed thatched roofs, Welsh timber cruck frames, and porcelain tiles.

This project hopes to create more habitation of ruins on the Anglesey coast as industrial and energy generation post linking into the greater ‘energy island’ project benefiting a socio-economic regeneration with equity to the local population.

Liverpool University

Jamie Hole, Ffion Douglas, Conor Foster, Holly Knight-Parfitt

Industrial Nouveau, Burnley

The project aims to demonstrate the capabilities of post-industrial territories along de-commercialised English waterways. The town in focus is Burnley, Lancashire, a once-booming 18th CE cotton textile town, residing along the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The project illustrates the potential of lost craft culture as a way to reignite a lost industry and local identity through a modern interpretation of textile production in light of the catastrophic environmental effects of ‘fast fashion’.

With cultural heritage and the environment in mind, the industrial model resides within four former 19th Century Textile Mills with the addition of further contemporary interventions that use an abstract reference methodology to contextualise among the historic masses. A restrained palette of timber, copper and mycelium brickwork compliment the historic stone structures.

Through a circular textile production system, 9000 tonnes of waste textiles are imported via canal annually and processed on site through reuse and immediate resale, recycling, and waste research systems. In doing so, the project prevents these waste textiles being burnt at landfill which would typically emit over 100,000 tonnes of CO2. The scheme utilises innovative technologies to break down typically difficult fibres such as poly-cotton blends through fungi beds leaving the polymer fibres and providing sugar-solutions for crop growth such as flax that can be used to reinforce and enhance new fabrics. This plant-based approach expands across the canal, transforming a dis-used car park into a biodiverse green space.

In a town suffering from social deprivation, the industry provides over 200 much-needed jobs to locals, and a further 300 available educational spaces that coincide with the neighbouring UCLAN university campus. Meanwhile, the intervention of the project opens up a new pedestrianised route from the neighbouring train station and residential area through to the town centre, creating greater engagement with the neglected canal waterway. While the reuse of the canal as a method of commercial transportation reduces the need for automotive transport, encouraging further pedestrianisation and reducing transport emissions. It is theorised that the approaches made to the project could be made to other towns along the canal and other historic waterways in England, utilising local industrial traditions as a method of urban regeneration and sustainable modernisation of their towns.

Sheffield School of Architecture

Elliot Forster

The Evelyn Urban Wood Guild

Set on Convoys Wharf, formerly Deptford Royal Dockyard, the project connects and strengthens a fragmented network of community foresters, timber producers and woodworkers, facilitating more productive and beneficial use of London’s underutilised and disposed trees through traditional woodworking, lumber production, regenerative forest stewardship, and various public-facing activity.

By addressing the interface between a wooded park, the forgotten wharf, and the Thames, the project re-activates the site, reconnects the community to their timber and trade heritage, and responds to wider issues of post-Brexit construction and the climate crisis, while informing an architectural language which celebrates the space between natural and industrial, and the diverse, holistic value of timber products and processes.

The main guild straddles the boundary between Pepys Park and the industrial wharf, and reflects this architecturally. On the park side, social and educational spaces relating to forestry sit within a tower, preserving space in the park while providing panoramic views to the landscape and varied relationships with the main hall, which is used for woodworking, education, commerce and exhibition, and links to productive elements on the wharf.

The natural-industrial duality informs the project’s material palette, creating a celebratory patchwork of local timber-based and grown materials where natural hand-jointed roundwood collides with engineered CLT insertions, and softer elements such as thatch, reclaimed bark and willow. This diverse palette is varied depending on use, character and activity.

Among the park, wharf and river, various productive and recreational landscapes are then established. While areas such as piers and market shelters serve the logistical needs of the guild, others such as the sapling nursery and weavers wetlands provide enjoyable space for accessible crafts and public activity, enticing younger or less industrially inclined users.

The duality also drives the detail response, where the fluctuating roundwoods incorporate embedded glulam fins, from which a modern envelope can be hung, achieving high performance while keeping the carefully crafted structure exposed. The secondary structure is also used to support the traditional thatch roof, and the various natural wall finishes which are prefabricated and cleat-hung.