Congratulations to our 5 finalists for the 3DReid Student Prize 2023:

- Julia Lauri De Funes – Leicester School of Architecture.

- Eloise Collier – Oxford Brookes.

- Eleanor Harding – The London School of Architecture

- Warren D’Souza – University of Bath

- Beatrice Ryan – University of Dundee

We received over 20 submissions and were incredibly impressed by the quality of work produced by all the students. It was a really enjoyable process looking through the huge variety of themes and styles that were covered in all the submissions.

The final will be held in our London Studio on Thursday 3rd August. Please see below for our 5 finalists’ entries.

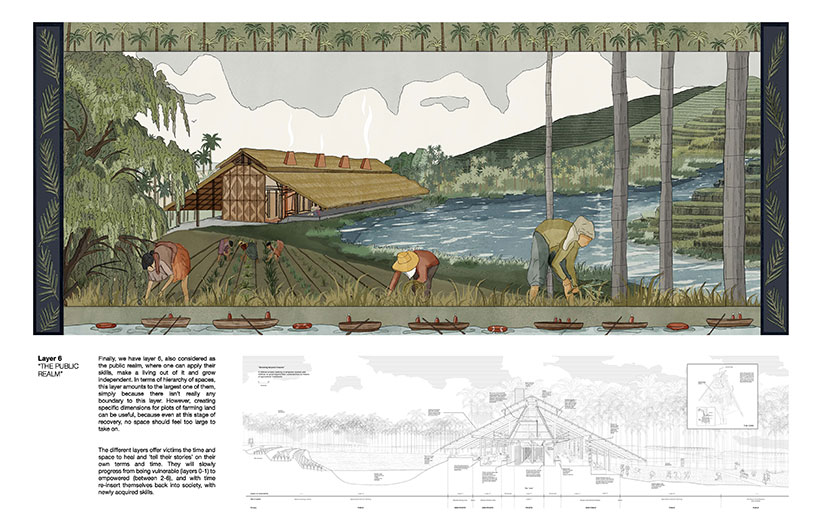

Julia Lauri De Funes, Leicester School of Architecture

A Ballet of Land, Sea and Life through Architecture

This year’s project, titled “A ballet of land, sea and life through sustainable architecture,” was driven by the theme of “Wild City” and the belief in the collaboration between architecture and nature to address challenges faced by the chosen location of Pedregalejo, a historic fishermen’s town in Malaga, Spain. The area had suffered from flooding due to the lack of breakwaters, and while their construction addressed the issue, it disconnected the community from the sea. The project aimed to address coastal erosion while promoting biodiversity by creating an artificial coral reef using biorock systems. The reef, designed to absorb wave energy, prevent erosion, and foster coral growth, became the focal point of the project. As the project progressed, a relationship between the architectural components and marine life was developed, and a parallel growth of terrestrial vegetation was encouraged on a designed roof, mirroring the materials and construction of the coral reef. This resulted in a blend of organic and artificial shapes. The main structure comprised three raised components: a reef structure construction workshop, a diving center, and a coral research center. The existing historic baths were repurposed as a restaurant, aiming to reconnect the community with the sea and revitalize the local economy. The rest of the coast was dedicated to a promenade, providing space for various activities such as fishing, sunbathing, surfing, and kayaking. The buildings’ structure and foundation were constructed using a timber framework and helical/screw piles due to the sandy ground. This project showcased a long-term strategy for coastal conservation that aligned with the “Wild City” ideal of collaborating with nature for a sustainable future. By encouraging the formation of coral reefs and eliminating the need for concrete barriers, it aimed to create a more biodiverse coastal community. The roof structure, constructed with recycled rebar materials, served the purpose of vegetation growth and blending with the coastal landscape. Additionally, the proposed building acted as a center for study, preservation, and conservation, raising awareness about marine ecosystems and offering educational opportunities for visitors. Moreover, this project served as a prototype for similar issues and areas around the Mediterranean Sea. By merging architecture and nature, it envisioned a sustainable future where coastal ecosystems thrive, and humans coexist harmoniously with their natural surroundings.

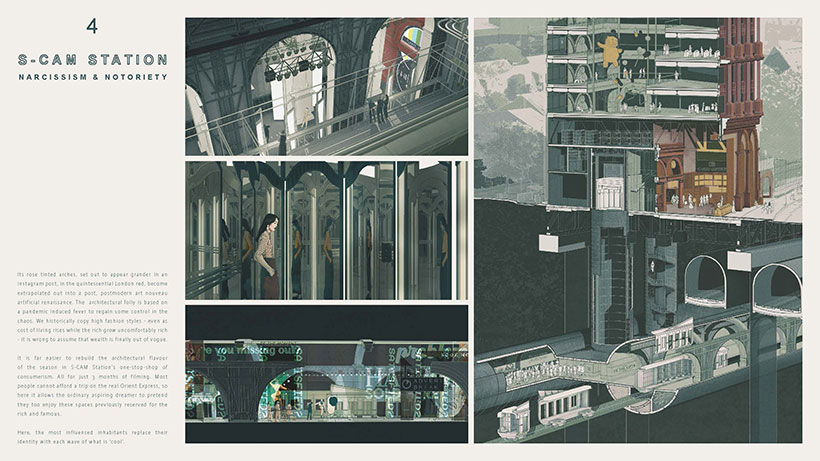

Eloise Collier, Oxford Brookes

S-CAM Station

A greenwashed project that observes society through architectural systems. Exploring over-consumption, social media, influencers and extreme capitalism.

Today’s generation is the most climate-conscious yet, but we have grown accustomed to wanting bigger, better, now. This dichotomy, along with the rising cost of living, has made living a commercial art where every moment can be captured and commodified. Since the world was reopened, train stations have become the new shopping mecca – a captured audience with a short attention span and an appetite for convenience. As urbanisation spreads, cities verticalize, and the connectivity of the iconic abandoned tube station is the perfect opportunity for capitalisation and branding.

As we chase popularity through cycles of trends, humans produce themselves into waste products, and the increasingly expensive city transforms essential services into commodities. Not least, the opportunity for decent housing. Shopping, living and commuting are often combined, as the price-tag on housing increases for a desirable connected area. While upmarket apartment blocks are required to include affordable housing in order to be granted planning permission, often performative heroics disguise the class divides that exist. There is a growing trend to segregate wealth with poor doors and separate lobbies in the high rises that were not able to skirt the planning authority with well-placed donations and a half-hearted attempt to offer an alternative location for housing.

S-CAM Station alludes to a romanticised past, offering notions of durability, solidity and timelessness in a time where planned obsolescence prevails. We are constantly influenced by media as a digital multiplex network that is powered by consumerism. All media has become an oligopoly – an industry controlled by a few large entities – where genuine intentions are rejected in favour of profit, and accountability is replaced by popularity online. Media and marketing are now rigidly intertwined, and the role of the influencer becomes spreading brand identity for profit. Our built environment now only needs look perfect online so the backdrops of the ultra-rich can appear to be democratised. But this pixelated separation obscures any lack of craftsmanship, keeping costs down – and profits high – for investors. The tower performs as a perfect stage set – when the angle is right.

What is considered frivolous must be taken seriously.

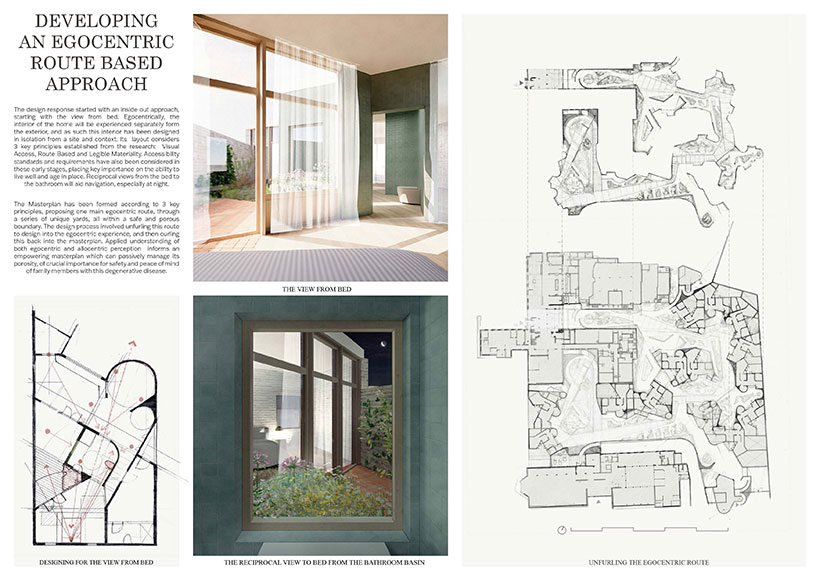

Eleanor Harding, The London School of Architecture

Nobody Wants to Live in a Care Home

In 2023, the widely reported Care Home Crisis is continuing to worsen, with a surge in ‘inadequate’ ratings following the COVID-19 Pandemic. This National crisis is happening behind closed doors, following years of cuts in the Social Care Sector. Care Homes are often located outside of our town centres, involving displacement from family and community life – an urban manifestation of our societal and historical approach to care.70% of all care home residents have Dementia, the most common variety being Alzheimer’s Disease. Approximately 5200 Londoners are living with the Young-Onset Alzheimer’s variety [meaning they are 65 years old or younger at the time of diagnosis]. These people often have young families, jobs and mortgages, meaning the typical institutional care system is not suited to them. Conversations with people living with Young – Onset Alzheimer’s at the London Assembly reveal a key desire to be respected as ‘People with a today and a tomorrow, not just a yesterday’.Architecture cannot cure Alzheimer’s. However, an architectural understanding of the spatial confusion associated with the disease presents an opportunity to radically reimagine a design approach for dementia spaces, prioritising quality of life and cognitive accessibility. This has been informed by the distinction between egocentric and allocentric spatial cognition: whereas a healthy brain takes egocentric, or point-of-view route-based spatial information, and forms an allocentric, or bird’s-eye cognitive map, studies of Alzheimer’s show this translation begins to break down, causing increased reliance on egocentric perception. This project asks how an architectural understanding of the effects of Alzheimer’s on spatial perception can be used to create better spaces for those living with the disease.A town centre site in Crouch End is the selected location for a pioneer project, designed through an egocentric lens, comprising of 33 homes for PWAs and their families, 2 porters lodges and route-based landscaping. Located near a thriving high street and the neighbouring community buildings of Hornsey Town Hall and Hornsey Library, it provides an ideal opportunity to test integration with existing community assets. While the project is sensitively site specific, the ambition is that the research and design approach can be replicated and applied extensively throughout London, the UK and internationally.

Warren D’Souza, University of Bath

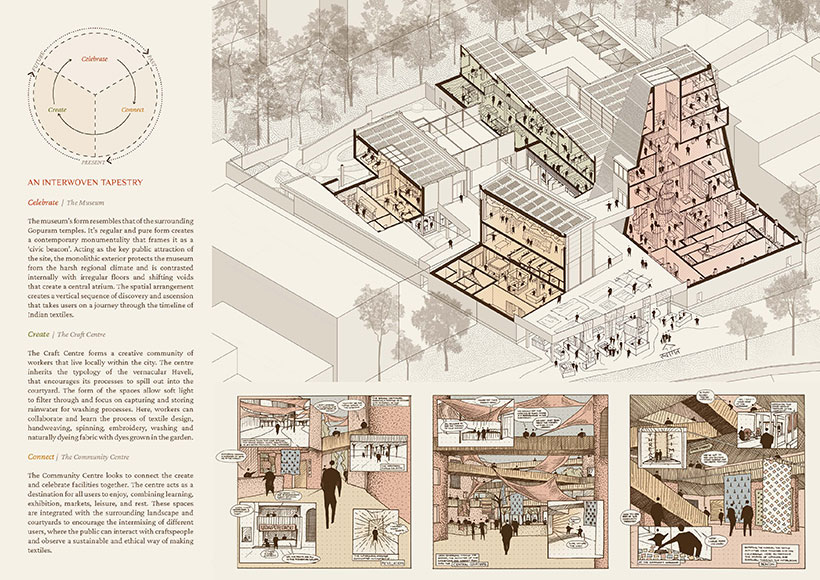

Threads of Time

The culture of the cloth has long been threaded through India’s history, with it being central to all aspects of society. From the cloth of the early Indus Valley civilisations to the khadi that became a national symbol of resistance, each fabric is emblazoned with an intrinsic sense of place and expression. However, the growing industry now faces surmounting challenges. Traditional techniques are being replaced by unsustainable and unethical processes that are fraying the threads that once symbolised the nation’s identity.

Located at the heart of Udaipur, on the border of its historic Old City, the project seeks to revitalise the lost textile bazaar by reconnecting the city with its textile roots and paving a future for the growth of Indian craftsmanship.

Adorned in a gradating pattern of bricks that resemble the weft and warp of the fabric, the Museum references the monumental Gopurams of the surrounding temples. Becoming its own ‘Civic Beacon’, the Museum will act as a cultural symbol that educates and enlightens the public on the city’s rich textile heritage. Users are taken on a journey through time, spiralling around an illuminated atrium that forms the vertical sequence. The glimmering red zinc facades that surround the museum resemble the characters and patterns of the local thread. These connected zinc volumes accommodate creative workshops, weavery spaces, and public amenities such as the library and market. Collectively, they form an interwoven network of discovery and education, cultivating an ethos of sustainable textile culture by promoting the circular journey of the fabric.

Rising from the earth, a social plinth unifies the typologies, creating an active ground plane through a series of connected landscapes that transition from the bustle of the bazaar to the release of the dye garden. Drawing from vernacular Haveli typology, courtyards are positioned to create localised microclimates that enhance the intermittent flow of activities between inside and out. The project seeks to resonate with its local populace by taking them on a journey, where tradition and innovation coalesce to support the sustainable fabric that stitches together the narratives of the city, its people, and its culture. By weaving together the threads of time, the project celebrates the heritage of the past, connects with the processes of today, and creates opportunity for a more sustainable future.

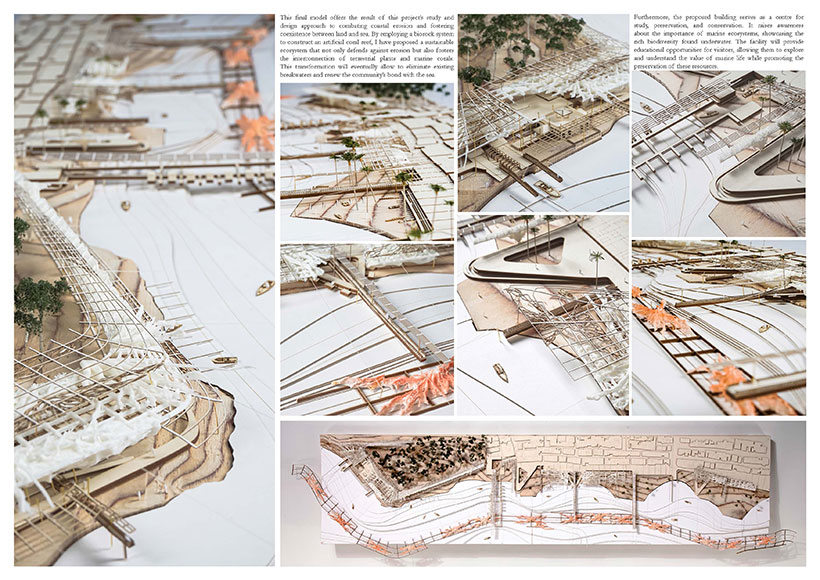

Beatrice Ryan, University of Dundee

Growing Beyond Trauma

During times of crises such as war, natural disasters, or pandemics, the existing gender data gaps in various areas are magnified and multiplied. And although men and women suffer from the same trauma, forcible displacement, destruction, injury, and death, women also suffer from female-specific injustices, such as sex trafficking, rape, domestic violence and prostitution. Gender based violence (GBV) refers to any violence inflicted from one gender to another. Unfortunately, internally displaced people (IDP) camps and GBV are often associated with one another, with GBV prevailing in such settings. Amongst other problems, the facilities lack privacy, safety measures and medical care, all of which can lead women to feel unsafe, exposed and vulnerable. These issues are often concealed because of the stigma surrounding this topic, and the women who have been unfairly subjected to abuse, continually struggle with trauma and self esteem. It has also been evidenced that rural women farmers in the Philippines are disadvantaged on other levels, making bad situations worse for them in the face of a disaster. However, the significant role of women in agricultural production can play a crucial part in the adaptation and mitigation of climate change in these sectors, if they are given the opportunity and support to do so. I am intrigued whether agriculture could be a catalyst to addressing the social issues faced by women in the context of a disaster prone city such as Tacloban. To what extent can architecture empower women to grow beyond their trauma by the means of agricultural livelihoods?

Our assumptions of hiding or running away suggests one is enclosed securely, but do we sometimes have to hide in plain sight? Is a door protection enough, or is distance, self-regeneration and empowerment, forms of protection? How can the design be suitable for different levels of vulnerability? I investigate the importance of intimate spaces in a shared setting, from physically testing out 1:1 spaces and by bringing the human scale at the forefront of this design research. I explore the value of cultural integrity and its significant contribution to empowerment, restoring livelihoods and maintaining a sense of home in a shared environment. Overall, the primary purpose of this research is to evaluate the specific needs of disadvantaged and vulnerable women, in order to then create a holistic approach that takes into account the challenges unique to them.