Nearly twenty five years since the publication of ‘Towards an Urban Renaissance’ we look back at one of the key questions raised by The Urban Task Force established by the Department for Environment of Transport and Regions and chaired by the late Architect Richard Rogers. How do we contain urban sprawl?

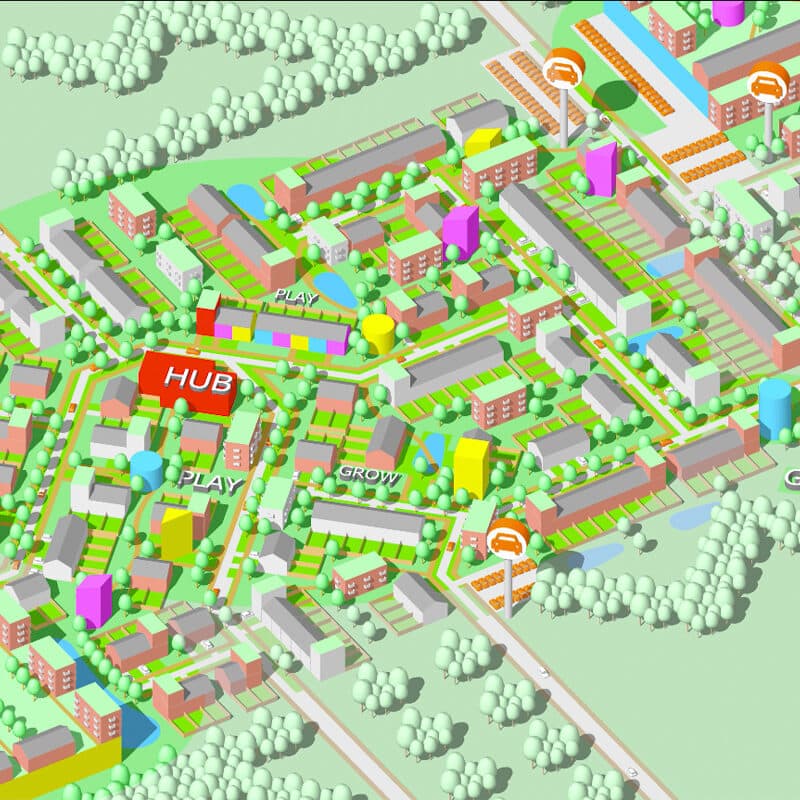

In the first of three Think Pieces based on this publication we explore the idea of reconfiguring suburbia to enhance wellbeing, increase the sense of community and diversify building uses whilst retaining the essence and qualities of suburban living. We were inspired to consider this topic in a modern-day context, accounting for the evolution of the construction industry and advances in technology including the emergence of automated transport.

Since the recent pandemic, the values prioritised in a home and neighbourhood have shifted to include access to nature and a need for greater spaces within our homes to allow for a separate workspace. These factors are symbiotic with aspects of the multi-faceted nature of well-being and include ownership of property, privacy, improved air quality, green spaces within a walkable vicinity, security, affordability and a supposed better quality of life for family. These are amongst a handful of reasons people are being drawn beyond the edge of the city. However, there are trade-offs when compared to a city lifestyle including: low density, a possible territorial nature that Oscar Newman dubbed ‘defensible space’, differences in social interaction and a high dependency on cars. The Urban Task Force’s report also denotes the English Suburban Experience “characterised by heavy dependence on separate zones for different uses, undermining its economic and social cohesion as well as impacting negatively upon the natural environment”.

Reducing urban sprawl and making suburban life more environmentally sustainable can work in tandem. Various studies have concluded that cities have a lower carbon footprint per capita compared to those living outside cities, albeit with a variance in data. Increasing density can lead to a lower energy consumption per person, but there is a critical mass. Numerous boroughs and local authorities have a higher footprint per capita whilst also having a greater population.

Amongst a plethora of other changes, a shift from density targets to a design-led approach has occurred with the aim to increase the potential of brownfield sites. Identifying specific zones where density can be increased in a subtle way can allow for a greater number of people to utilise existing infrastructure but also create pockets for communal open places and flexible spaces. However, this has consequences. A denser population may not be sustainable if there is a homogeneity of uses.

Akin to nature, a diversity of uses can reap economic, environmental and social benefits. It allows for a variety of amenities to be incorporated within a closer vicinity to a greater number of residents. Distributing these uses also has the potential to induce a socially optimal solution within economic game theory. ‘Mixed-use’ can also “contribute to reducing feelings of isolation and depression”, whilst adding to the sense of local identity. These amenities have to be carefully dispersed and designed and can include nurseries, grocery stores, clinics, leisure areas, work hubs etc.

The National Transport Survey shows the more rural the area, the greater the requirement for cars and private transport. Pedestrianisation not only creates safer places but also creates areas which facilitate social activity. This includes play for children. Designated zones for car parking encourages residents to walk to their cars, and possibly continue walking to their destination if the extra time and effort is marginal. Furthermore, opportunities are created to host communal events.

Connectivity is crucial. The carbon footprint will likely be much lower when there are alternative ways to access areas of necessity, which will require investment in local infrastructure. Disparate amenities scattered without thought can be detrimental. A mixture of uses not easily accessible by foot, cycle or public transport can render the benefits of pedestrianisation futile.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution and depending on certain areas, some of the points mentioned above can be easily challenged. It is important to note however that cities may not be the answer to a more sustainable way of living as they currently have their own problems including: air quality, higher levels of stress, lack of green and blue infrastructure, etc. As designers, we recognise what makes up the identity of a place and where the value is focused for that respective community.

Only by challenging existing ideals and perceptions can we create more sustainable, adaptable and ultimately enjoyable lifestyles outside of our towns and cities…